In 1936, [Howard] Aiken had proposed his idea [to build a giant calculating machine] to the [Harvard University] Physics Department, … He was told by the chairman, Frederick Saunders, that a lab technician, Carmelo Lanza, had told him about a similar contraption already stored up in the Science Center attic.

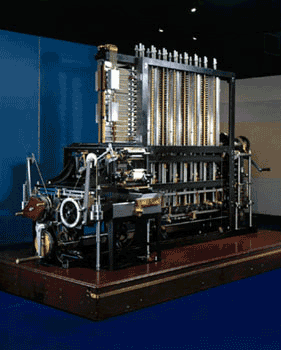

Intrigued, Aiken had Lanza lead him to the machine, which turned out to be a set of brass wheels from English mathematician and philosopher Charles Babbage’s unfinished “analytical engine” from nearly 100 years earlier.

Aiken immediately recognized that he and Babbage had the same mechanism in mind. Fortunately for Aiken, where lack of money and poor materials had left Babbage’s dream incomplete, he would have much more success

Later, those brass wheels, along with a set of books that had been given to him by the grandson of Babbage, would occupy a prominent spot in Aiken’s office. In an interview with I. Bernard Cohen ’37, PhD ’47, Victor S. Thomas Professor of the History of Science Emeritus, Aiken pointed to Babbage’s books and said, “There’s my education in computers, right there; this is the whole thing, everything I took out of a book.”

The Harvard University Gazette. Howard Aiken: Makin’ a Computer Wonder By Cassie Furguson

The quote is incorrect. The “brass wheels” were a small demonstration piece for the Difference Engine I not the Analytical Engine. They were one of six such pieces constructed by Babbage’s son Henry after his fathers death. These demonstration pieces were distributed among various universities including Harvard. Aiken must have been sufficiently intrigued by the mechanism to investigate Babbage. In the course of this investigation he would have discovered Babbage’s Analytical Engine and the similarities it bore to his own machine. It is not clear when Aiken was given Babbage’s “books” or indeed what they contained. They did not contain plans of the Analytical Engine since the only plans have always been stored at the Science Museum at Kensington in London. Aiken may have been able to obtain some of the following documents which together comprise the complete published account of the Analytical Engine

- Sketch of The Analytical Engine Invented by Charles Babbage. By L. F. Menabrea of Turin, Officer of the Military Engineers from the Bibliotheque Universelle de Geneve, October, 1842, No. 82. With notes upon the Memoir by the Translator Ada Augusta, Countess of Lovelace.

- Passages from the Life of a Philosopher. Chapter VIII. Of the Analytical Engine by Charles Babbage. 1864

- Report of the Committee, consisting of Professor Cayley, Dr. Farr, Mr. J. W. L. Glaisher, Dr. Pole, Professor Fuller, Professor A. B. W. Kennedy, Professor Clifford, and Mr. C. W. Merrfield, appointed to consider the advisability and to estimate the expense of constructing Mr. Babbage’s Analytical Machine, and of printing Tables by its means. Drawn up by Mr. Merrifield. 1878

- The Analytical Engine, paper by Major-General Henry P. Babbage (Charles Babbage’s son), read at Bath on September 12th, 1888; published in the Proceedings of the British Association, 1888.

- Babbage’s Analytical Engine. By Major-General H. P. Babbage. 1910 April 8. From the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 70, 517-526, 645 [Errata] (1910). -[ via The Foumilab Analytical Engine website the best website concerning the Analytical Engine]

These documents along with Babbage’s “books” would have given Aiken a high level description of Babbage’s planned machine.

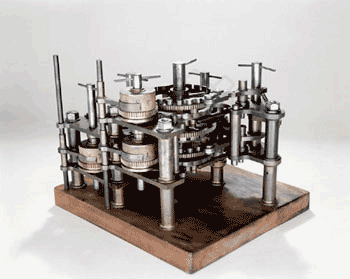

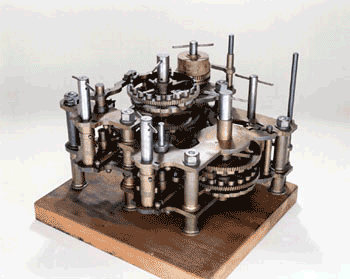

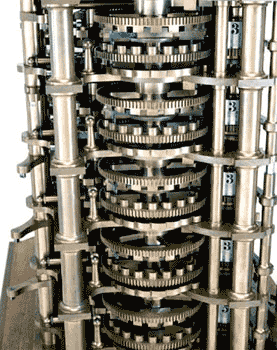

The pictures below show front and rear views of one of six demonstration pieces for the Difference Engine I created by Henry Babbage after his Fathers death. This piece is similar to the one shown to Howard Aiken in 1936

Aiken may also have seen photographs of the largest test piece of the Difference Engine I held by the Science Museum, Kensington, London, UK.

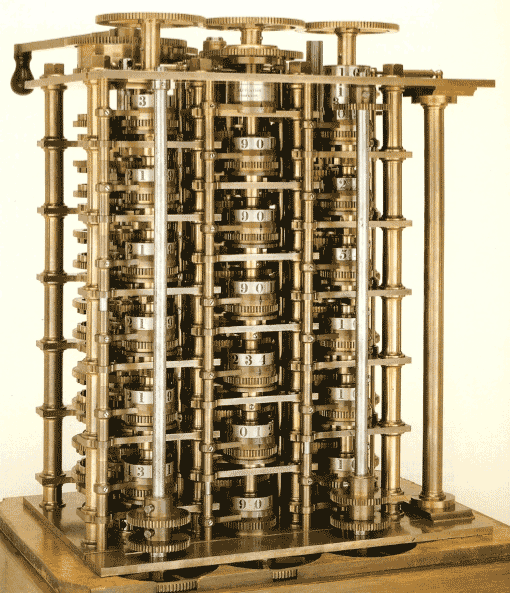

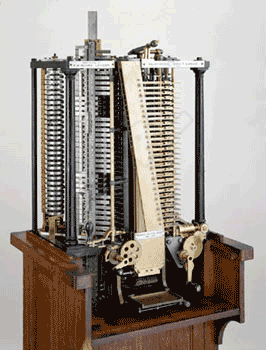

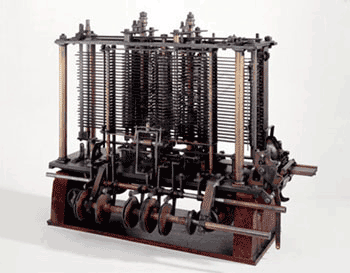

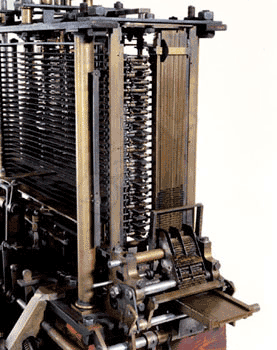

Two large fragments of the Analytical Engine were constructed by Babbage’s son and Aiken may have seen photographs or otherwise become aware of their existence.

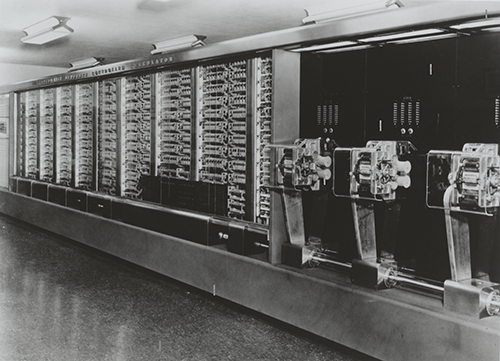

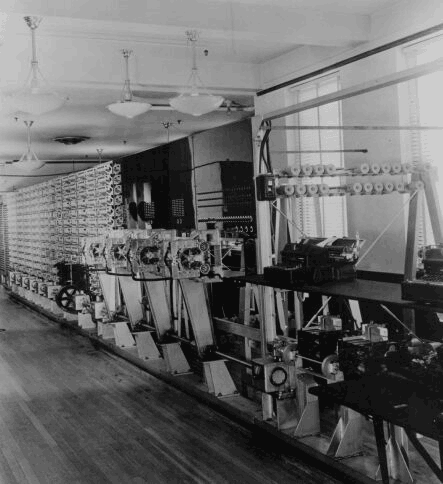

In 1991 the Science Museum in London constructed the Difference Engine II, the printer was added in 2001. These pieces are on display in the Museum, which is well worth a visit. The construction of the Difference Engine II is documented by Doron Swade in his book The Difference Engine Charles Babbage and the quest to build the first computer. The Difference Engine II was the last machine Babbage designed and employs lessons he learned from both the Difference Engine I and the Analytical Engine. For example the printer was designed for use by the Analytical Engine and Babbage reused it for the Difference Engine II. The similarity between the Difference Engine II and the machine that Aiken built is striking. Note the drive shaft running along the bottom of both machines and the general arrangement with printers at one end of a long tall frame. This may be the result of convergent evolution rather than direct influence but the similarity is still striking.

In the foreword to the manual for the operation of the Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator (ASCC) Howard Aiken states that “The appendices were prepared by Lieutenant [Grace] Hopper” with the assistance of others and that “[She] acted as general editor, and more than any other person is responsible for the book.” It seems safe to conclude that Howard Aiken and Grace Hopper were not only influenced by Charles Babbage but they and their team held him in high regard and considered themselves guardians of his reputation and inheritors of his quest.

Chapter 1. Historical Introduction

“If, unwarned by my example, any man shall undertake and shall succeed in really constructing an engine embodying in itself the whole of the executive department of mathematical analysis upon different principles or by simpler mechanical means, I have no fear of leaving my reputation in his charge, for he alone will be fully able to appreciate the nature of my efforts and the value of their results.”

Charles Babbage The Life of a Philosopher (1864)

The Manual of Operation for the Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator. By the staff of the Computation Laboratory with a forward by James Bryant Conant. Cambridge, Massachusetts. Harvard University Press. 1946.

The staff of the Computation Laboratory at the time the ASCC manual was published in 1946 are listed below. They went on to have a considerable influence on the development of the modern computer. Not least of which was Grace Hooper who developed the first compiler and several popular languages.

- Comdr. Howard H. Aiken USNR. Officer in Charge

- Lt. Comdr. Hubert A. Arnold, USNR

- Lt. Harry E. Goheen, USNR

- Lt. Grace M. Hopper, USNR

- Lt(jg) Richard M. Bloch, USNR

- Lt(jg) Robert V. D. Campbell, USNR

- Lt(jg) Brooks J. Lockhart. USNR

- Ens. Ruth A. Brendel, USNR

- William A. Porter, CEM

- Frank L. Verdonck, YI/c

- Delo A. Calvin, Sp(I)I/c

- Hubert M. Livingston, Sp(I)I/c

- John F. Mahoney, Sp(I)I/c

- Durward R. White, Sp(I)I/c

- Geary W. Huntsberger, MMS2/c

- John M. Hourihan, MMS3/c

- Kenneth C. Hanna

- Joseph O. Harrison, Jr.

- Robert L. Hawkins

- Ruth G. Knowlton

- Eunice H. MacMasters

- Frederick G. Miller

- John W. Roche

- Robert E. Wilkins

The influence of both, Howard Aiken, and the IBM ASCC – Harvard Mk I machine, on the later development of computers should not be over stated. The published notes from The Moore School Lectures (held in 1946) are rather scathing with respect to Aiken and his understanding of the direction in which the new electronic computing machines would lead.

Hartree was very forward looking and was excited by the mathematical potential of the stored program computer. On the other hand, Aiken was absorbed in his own way of doing things and does not appear to have been aware of the significance of the new electronic machines.

The Moore School Lectures (Charles Babbage Institute Reprint)

Unlike Aiken and his machine, Grace Hopper and some of her colleagues went on to have a significant influence in the early development of compilers and language design. One wonders what if any influence Babbage and Ada Lovelace had on Grace Hopper’s ideas. Unfortunately I can find no comments by Hopper regarding either Babbage or Lovelace.

[ Pictures via The Science and Society Picture Library]